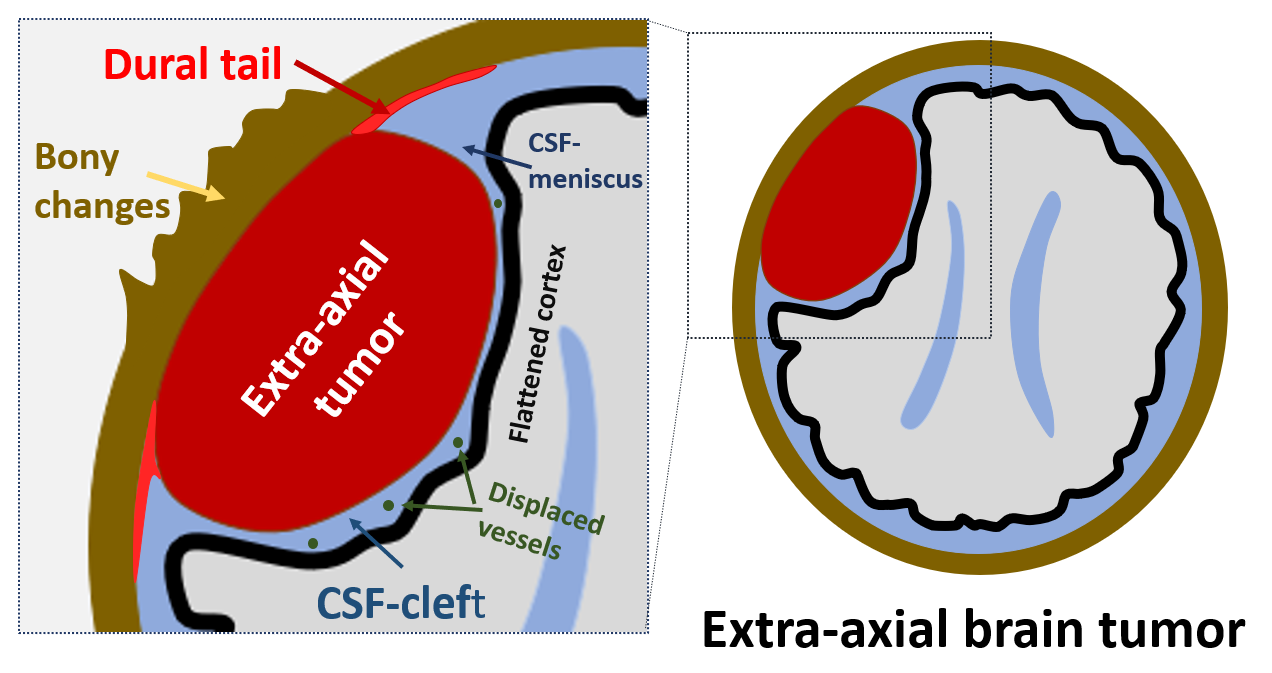

When confronted with an intracranial mass on imaging, the first thing you have to do is determine the exact location of the tumor, more specifically: whether the tumor is located inside the brain parenchyma or outside the brain parenchyma. A tumor located inside the brain parenchyma is called an “intra-axial” brain tumor, a tumor outside the brain parenchyma is an “extra-axial” brain tumor.

There are a lot of tips and tricks you can use to make that distinction. The most reliable sign is the CSF-cleft sign. Other signs that are suggestive for an extra-axial tumor, but less specific, are the dural tail sign and bony changes such as hyperostosis. Let’s start with the CSF-cleft sign.

The CSF-cleft sign. A CSF-cleft is a thin rim of cerebrospinal fluid between the tumor and the brain parenchyma, and is the most reliable imaging sign indicating an extra-axial brain tumor. On the images below we see a large T2-hyperintense mass in the posterior fossa on the left side, corresponding to a meningioma. There is a small rim of T2-hyperintense cerebrospinal fluid visible between the tumor and the left cerebellar hemisphere. This is a CSF-cleft sign. Notice that the tumor also erodes the left occipitak skull bone.

The CSF-cleft can be seen on all imaging sequences, and sometimes even on CT, but is often most conspicuous on T2-weighted images. The CSF-cleft can contain small subarachnoid vessels, so the presence of displaced vessels between the tumor and the brain parenchyma is an extra argument in favor of an extra-axial mass. the CSF-cleft may be wider at the edges of the tumor-brain interface, and this subarachnoid space widening is sometimes referred to as the “CSF-meniscus sign”. As the cortex is located on the outher surface of the brain in both the cerebrum and the cerebellum, often a rim of flattened cortical tissue can be seen immediately underneath the extra-axial tumor.

The T2-weighted image above shows a very large bifrontal T2-isointense extra-axial mass. There is clear CSF-cleft sign between the tumor and the underlying brain parenchyma. Notice how the CSF-cleft widens at the edges of the tumor, giving rise to a triangular “CSF-meniscus” on both sides of the tumor. Also notice the precence of several punctate flow-voids in the CSF-cleft between the mass and the bifrontal brain parenchyma. These are displaced subarachnoid vessels. Lastly, there is thin rim of flattened, compressed cortex visible immediately underneath the tumor, best appreciated on the left side.

The dural tail sign is another sign that can often be seen in extra-axial tumors, especially meningiomas. The dural tail sign refers to thickening and contrast enhancement of the dura immediately adjacent to an (extra-axial) tumor. The enhancement of the dural tail is often more pronounced than the enhancement of the actual extra-axial tumor, and is thickest immediately next to the tumor.

On the images above we see a small left frontal convexity meningioma. On the unenhanced T1-weighted image (left) we see a clear CSF-cleft between the tumor and the underlying left frontal lobe. We also see compressed and somewhat flattened cerebral cortex underneath the tumor. On the contrast enhanced T1-weighted images (right) there is homogeneous enhancement of the tumor, but also contrast enhancement of the dura medial and lateral from the tumor (arrows) corresponding to the dural tail sign. Notice that that the dural tail enhances stronger than the actual tumor.

What is the dural tail sign? What does it correspond to? Contary to what has often been said, the dural tail sign does not correspond to tumor invasion of the dura, but probably reflects venous congestion and reactive edema of the dura. Also, a dural tail sign is not pathognomonic for meningioma. True, the dural tail sign is most often seen in meningiomas, but the dural tail sign can also be seen in a lot of other tumors, even intra-axial tumors. Basically any tumor that contacts the dura, including superficially located intra-axial tumors, can invoke reactive edema in the dura and a dural tail sign. Just take a look at the images below.

These images are contrast-enhanced T1-weighed images belonging to two patients with a CNS-lymphoma (left image) and a glioblastoma (middle image), respectively. Both tumors are intra-axial tumors, but in these two patients the tumors are located superficially in the brain parenchyma and make contact with the dura. Thickening and contrast enhancement of the dura can be seen where the tumor abuts the dural surface, resulting in an appearance similar to the dural tail sign (arrows in the zoomed-in images on the right).

Bony changes such as hyperostosis and lysis can also be seen in extra-axial tumors. Due to their superficial location and proximity to the skull, extra-axial tumors can induce bony changes in the overlying skull. Hyperostosis is more frequent than lytic changes. Hyperostosis is focally increased bone formation in the skull induced by an underlying tumor, most often a meningioma. Hyperostosis can be very pronounced and may even look very agressive. A “bump on the head”due to hyperostosis is somtimes the presenting symptom of patients harboring a meningioma. Lytic changes are less frequent, and when lytic skull changes are seen, more agressive tumors (such as dural metastsis, hemangiopericytoma…) have to be considered. Beware, bony changes are not pathognomonic for meningioma, and not even for extra-axial tumors, but can occur in any tumor that contacts the skull, including superfically located intra-axial tumors.

Hyperostosis. On the CT above (left image) extensive hyperostosis of the left frontal and parietal bone can be seen. Contrast-enhanced T1 (right image) shows linear dural contrast enhancement immediately underneath the area of hyperostosis (black arrows). This is a so-called “en plaque” meningioma. En plaque meningiomas are thin sheetlike meningiomas that despite the fact that often induce extensive hyperostosis in the overlying skull bone.

Skull lysis. On the CT above (left image) we see a large lytic defect centrally in the occipital bone. We can also see a large tumor extending through the skull defect in the subcutaneous tissue. On contrast-enhanced FLAIR image (right image) we see an extra-axial tumor (notice the small CSF-cleft between the cerebellum and the tumor) containg several punctate flow voids (so it’s probably a hypervascular tumor) and extending through a lytic skull defect into the occipital subcutaneous tissues. This was a high grade solitary fibrous tumor of dura (hese tumors used to be called “hemangiopericytomas) and are agressive dural tumors that can look a lot like meningiomas, but contrary to meningiomas are often associated with erosion of the overlying skull.

LET’S SUMMARIZE:

- The CSF-cleft sign is the most important radiological sign indicating an extra-axial tumor. A CSF-cleft is a thin layer of cerebrospinal fluid between the tumor and the brain parenchyma. Within this CSF-cleft, subarachnoid arteries and veins can also be seen, and the CSF-cleft may be wider at the edges of the tumor-brain interface (CSF meniscus sign).

- The dural tail sign and involvement of the skull (hyperostosis or lysis) can be observed in any tumor that come into contact with the meninges or the bony skull. A dural tail and bone involvement are more commonly seen in extra-axial tumors, especially meningiomas, but they can also be seen in superficially located intra-axial tumors.

Have any remarks, questions, feedback, tips or tricks of your own to share? Please leave a comment!